ATHENS, Ohio — After 40 years of rehabilitation efforts, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources has recognized Raccoon Creek as one of the state’s scenic rivers.

ODNR Director Mary Mertz and Gov. Mike DeWine designated Raccoon Creek Ohio’s 16th state scenic river Nov. 12. Raccoon Creek is the first stream in southeast Ohio to receive the designation.

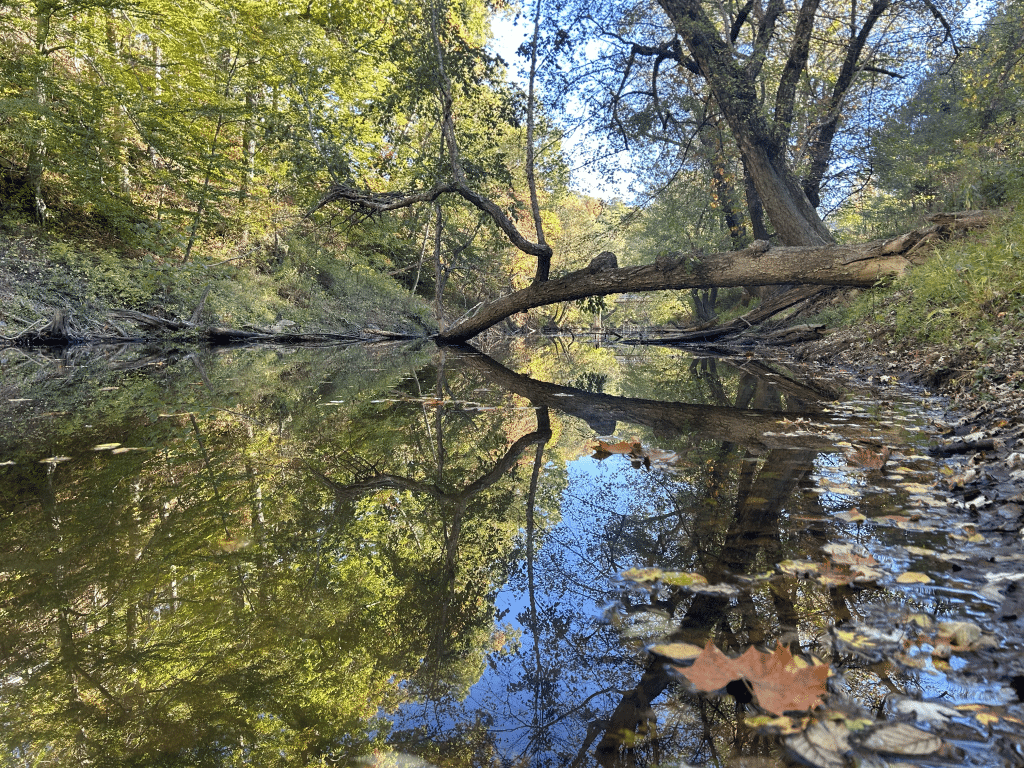

“This is a very special place, and we need to treat it as a special place,” DeWine said at the designation ceremony. He described Raccoon Creek as a beautiful stream with a powerful comeback from decades of pollution from previous mining activity in the watershed.

“It’s a recognition, formal recognition, of all the work that’s been done over many years to really restore this creek. It took a lot of people, it took a lot of resources,” said DeWine.

Mertz also expressed gratitude for everyone who contributed to the stream’s recovery.

“The journey to it becoming a state scenic river began decades ago, thanks to the concern of caring Ohioans who wanted to restore beauty to this neglected and degraded watershed,” said Mertz.

Raccoon Creek is one of the longest streams in Ohio, according to Raccoon Creek Partnership, a local nonprofit group that has been instrumental in restoring the creek’s water quality. It begins near the village of New Plymouth in northern Vinton County and travels 112 miles until discharging into the Ohio River south of Gallipolis.

The Ohio Scenic Rivers program is intended to protect and preserve the state’s few remaining high-quality, natural rivers and streams through collaboration with local businesses, landowners, organizations and other state and federal agencies, according to ODNR’s website.

ODNR has been categorizing Ohio’s waterways since the passage of The Ohio Wild, Scenic and Recreational River Act in 1968. The bill was the first of its kind in the country, predating the National Wild and Scenic River Act, according to ODNR’s website.

Ohio rivers can be classified as wild, recreational or scenic. Wild rivers are generally inaccessible, with undeveloped flood plains and highly forested stream corridors. Recreational rivers receive protection for their “unique cultural and/or important historical attributes,” according to ODNR’s website, and do not retain as much natural character because there is apparent human activity.

Scenic rivers — Raccoon Creek’s designation — fall between the two classifications. Scenic rivers must retain much of their natural character: The stream and shorelines have little to no development and feature a substantial forested stream corridor.

The designation celebrates Raccoon Creek’s natural scenery, biodiversity and social significance. But until recently, Raccoon Creek didn’t fit the image of a state scenic river. In fact, the 92 species of fish that thrive in the stream today couldn’t exist there 40 years ago.

The rehabilitation of Raccoon Creek

Raccoon Creek was polluted with acid mine drainage as a result of a century of mining throughout the watershed. Acid mine drainage occurs when sulfur-bearing minerals or rocks, such as coal, are exposed to oxygen and water. The chemical reaction forms sulfuric acid and leaches toxic metals, such as iron and aluminum, into the waterway, making the water appear orange, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Normal water has a neutral pH of between 6 and 8, but acid mine drainage reduces its pH to around 3 — the same acidity level as orange juice. This acidic water cannot support fish or macroinvertebrate life, according to Raccoon Creek Partnership.

The stream’s acidity level has stabilized thanks to over 40 years of restoration and reclamation projects by Raccoon Creek Partnership. That work includes 22 projects funded by $17 million in grants from ODNR, the Ohio EPA and Ohio University’s Voinovich School, according to ODNR’s Scenic River Designation Study of Raccoon Creek.

Nora Sullivan, an environmental specialist at the Voinovich School, has assisted with restoration work since 2016, and previously served as a board member of Raccoon Creek Partnership.

“The town of Vinton in Gallia County is exceptional warmwater habitat, which is higher than our restoration goal. The rest of the main stem is warm water habitat, which is the goal,” Sullivan said, referring to the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency’s tiered aquatic life use designations.

Those designations categorize sections of waterbodies by their potential to support aquatic life and macroinvertebrates, according to the EPA. In 2016, the agency performed a biological and water quality study of Raccoon Creek, the first since 1995.

The study found that all of Raccoon Creek had improved, with aquatic life use designations jumping to the highest and second-highest ratings. The situation could improve further, the report noted, if the Vinton Dam in Gallia County was removed; the dam is a barrier to fish passage, with 18 species of fish found exclusively downstream of the dam.

Ohio EPA attributes the water quality improvements to Raccoon Creek Partnership’s work, which began in the 1980s when concerned citizens in Gallia County came together to discuss improving the stream’s water quality. The newly formed Raccoon Creek Improvement Committee began to educate residents about the stream’s water quality and organize cleanup events. But they quickly realized that truly remediating the stream would require extensive collaboration and funding.

By the 1990s, their efforts and members spanned all six counties in the creek’s watershed: Athens, Hocking, Meigs, Gallia, Vinton and Jackson. The committee acquired grant funding and state agency partnerships necessary to sustain restoration efforts. And in 2007, the group officially became the member-based, nonprofit Raccoon Creek Partnership.

The most impactful project is the Carbondale Doser, an active treatment system that dispenses 900 pounds of calcium oxide daily into Hewett Fork, a tributary of Raccoon Creek, said Amy Mackey, Raccoon Creek Watershed coordinator at the Voinovich School.

Other projects involve passive treatments, such as restoring wetlands that naturally filter contaminants over time, and “burying” coal spoil piles and sowing the area to prevent water from directly contacting the abandoned mine materials.

The success of those projects allowed Mackey to begin the process of securing a scenic river designation for Raccoon Creek in 2018. The first step was working with Ohio University students to write letters about the designation’s benefits to watershed groups, elected officials and others.

“We basically flooded Bob Gable (the Ohio Scenic Rivers program manager) with letters,” Mackey said.

The letters must have piqued interest. In 2020, Mackey met with ODNR officials — Matthew Smith, the East region manager of ODNR’s scenic rivers program — to convince them that Raccoon Creek was no longer a dead stream.

Smith couldn’t believe Mackey was talking about the same orange stream he remembered sampling in the ’90s while attending Ohio University.

“There was no way you would have ever thought, ‘Let’s look at Raccoon Creek and designate it,’” Smith said.

That’s because the program is intended to designate streams of high quality, not streams that need to be restored. Smith said the prevalence of acid main drainage in waterways like Raccoon, Monday and Sunday creeks have kept the region’s waterways from achieving official designations.

“It’s such a success story, the success of recovery and, you know, the other scenic rivers haven’t had to deal with that,” Smith said.

Mackey also attended township trustee meetings to talk about the potential designation. That was an easy sell: “Everybody wants to show me a picture on their phone of the fish they’re catching in Raccoon Creek,” Mackey said.

Smith said that a scenic river label often spurs tourism because people want to see the natural beauty themselves. But this is not the only benefit of a designation, Smith said. ODNR becomes a conservation partner, an educational outreach resource, a grant-writing assistant and more.

For example, Conneaut Creek, located in northern Ashtabula County, was designated in 2005 and draws tourism in the fall when steelhead trout migrate to the stream for the winter. ODNR has helped purchase public land to make fishing in Conneaut Creek more accessible, thus drawing more recreation, Smith said.

Recreation along Raccoon Creek

Bobbi and Dustin Hoy own Raccoon Creek Outfitters, a canoe livery and recreation equipment shop in Albany. Bobbie Hoy attributes the livery’s success to Raccoon Creek Partnership’s restoration work.

“If it wasn’t for them, absolutely [this would not be] a canoe livery,” she said.

They tried to open the business originally in 2007. But, Bobbi Hoy said, their loan applications were denied because “everybody told us, ‘It’s not going to work: There’s no money in kayaking.’”

They finally opened the doors in 2017. The livery has been extremely successful, she said: In most years, they reach their goal of 1,500 paddlers a season.

Part of the work involved clearing away debris from fallen trees that made the creek unnavigable for kayakers.

“Everybody’s been really happy with us being here, yeah, partly because we cleaned this place up so much, and we keep the creek clean so, like, they can just jump on the water and paddle,” Bobbi Hoy said.

The Hoys have created an entire recreation market around Raccoon Creek, selling kayaks, canoes and fishing equipment. Their site also offers overnight camping, with plans to eventually install cabins on the property.

“The more people we can get out here enjoying it, the better,” Hoy said.

In 2012, Shannon Mayes started a Gallia County chapter of Trout Unlimited to teach fly-fishing to young people. The program is a part of the national TU nonprofit dedicated to “conserving, protecting and restoring America’s coldwater fisheries and their watersheds,” according to its website.

He expected to attract five students. Today, Mayes works with 35 young people, teaching them to fish and taking them on fishing trips around the country. He estimated he spends 250 days a year working with his students, plus another 150 and 175 days a year fly-fishing on his own.

The club primarily fishes in Raccoon Creek and Little Raccoon Creek.

“It’s good fishing, and it’s kind of a hidden gem,” Mayes said.

Mayes said that while he appreciates having the stream largely to himself and his students, he welcomes the designation’s potential to bring more visitors to appreciate the stream’s beauty and biodiversity.

“We have a lot of great things in Gallia County, and I think having a scenic waterway, the Racoon Creek, running through our county, is just one more highlight to our area,” he said.

Let us know what's happening in your neck of the woods!

Get in touch and share a story!