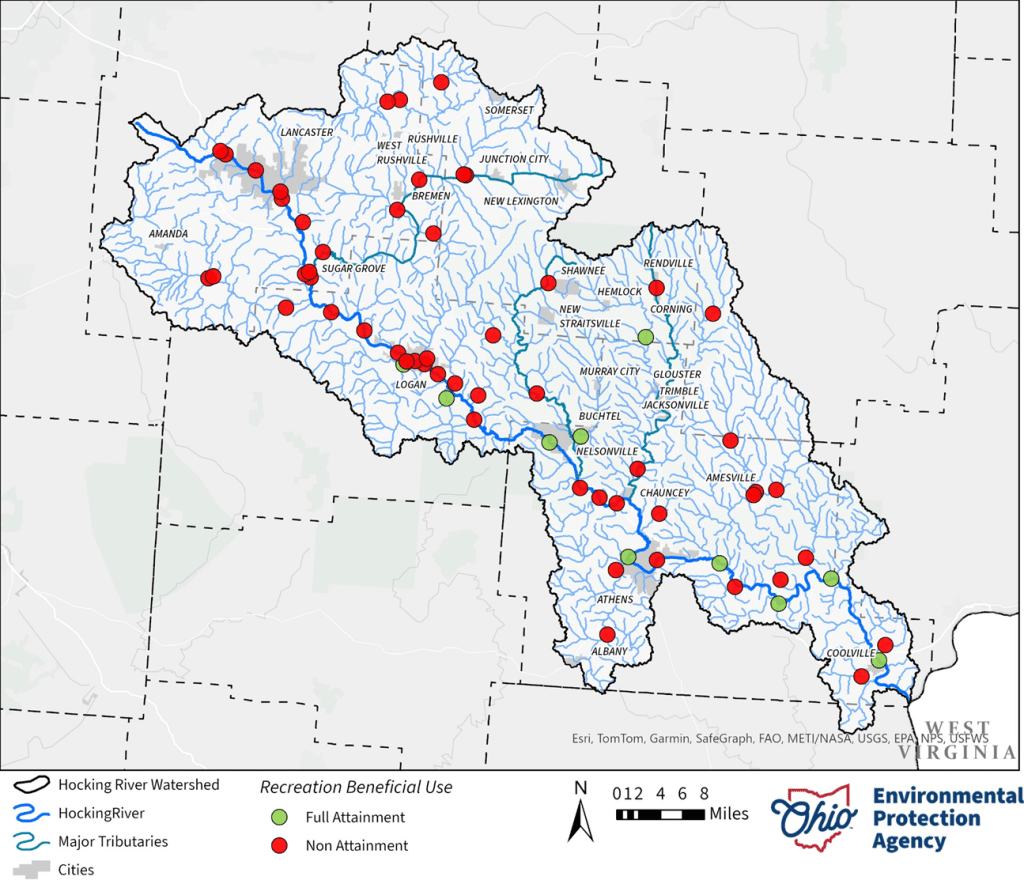

ATHENS COUNTY, Ohio — While the Hocking River may be an ideal environment for fish and invertebrates, it’s not safe for humans — at least not yet. Testing of water samples revealed high levels of E. coli in the Hocking River, with only 10 sites meeting recreational water quality standards.

Swimming or wading in water contaminated with E. coli can lead to diarrhea, vomiting, and a variety of infections, according to the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

E. coli can come from numerous sources, including livestock waste. In recent tests, Margaret Creek in Albany had high E. coli levels because cattle get into the creek. However, the Ohio EPA doesn’t have regulatory authority over these sources, so it must work with other state agencies to resolve these issues.

“We can’t go and tell a farmer, ‘You have to do this,’” said Kelly Capuzzi, an environmental supervisor at the Ohio EPA.

Instead, the agency will work with the Ohio Department of Agriculture’s Soil and Water Division, which has funding to build fences along streams or to provide alternate water sources.

“But it’s a voluntary program,” Capuzzi said

Wastewater treatment plants were once the main culprit, but improving technology and investment in infrastructure have resolved these issues, said Ohio EPA Director Anne Vogel.

“Thirty years ago, you might have seen raw sewage in a lot of our waterways,” Vogel said. “As we’ve been permitting our point sources for wastewater treatment plants, we’ve really seen an improvement statewide in terms of water quality, and the same is true on the Hocking.”

Today, the main sources of E. coli in water is private septic systems. A 2013 report from the Ohio Department of Health found that 31% of home sewer systems were failing, dumping an estimated 120 million gallons of wastewater everyday.

Dr. Natalie Kruse Daniels, a professor in Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Service, wasn’t surprised to hear about the high E. coli levels, noting that the recreational water quality standard has strict requirements.

“You have that potential for failing septic systems, under treated or poorly treated sewage, that kind of contributed to [E. coli levels],” Kruse Daniels said. “So no, it’s not really surprising, and it does suggest that there is an ongoing need for support for wastewater treatment in the region.”

Failing home septic systems present a complex issue for the Ohio EPA. The agency is responsible for monitoring surface water quality and regulating public wastewater treatment, but private septic systems are regulated by local departments of health.

In 2019, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine launched the H2Ohio program to raise awareness and fund projects looking to prevent algal blooms on Lake Erie and replace failing septic systems. In Athens County H2Ohio has given over $500,000 for U.S. Route 50 sewer project and equipment grants for water providers.

Several Southeast Ohio counties such as Hocking, Ross and Jackson have seen their health departments get H2Ohio funding to repair home septic systems. Patrick McGarry, the director of environmental health for the Athens City-County Health Department, thinks it’s only a matter of time until H2Ohio funding comes to Athens County.

“The latest was Hocking County,” McGarry said. “I’m in contact with all of our regional health departments and it sounds like they’re cycling around to hit different areas. So I fully anticipate that it will come [to Athens County].”

McGarry estimated that there are 10,000–12,000 home septic systems in Athens County. McGarry speculated that the most common and obvious source of septic pollution would be older septic systems using aeration tanks that discharged directly into waterways that feed into the Hocking River.

“Prior to 2007, state rules allowed for health departments to permit and allow for the installation of this aeration tank to a stream discharge, and that discharge could be directly to a stream, to the river, could be to a drainage pattern, could be to the roadside ditch,” McGarry said. “So we have quite a few of those.”

The Athens City-County Health Department is involved in several programs that seek to update septic infrastructure. In 2015, the health department required all new septic systems be signed up for a five-year maintenance inspection program that ensures the systems are in working condition.

Systems that were installed before 2015, however, can’t be enrolled in the inspection program until the property goes up for sale or a nuisance complaint is made. McGarry estimated that there are about 2,000 septic systems enrolled in the program so far.

The health department also receives $150,000 in every grant cycle from the Ohio EPA Water Pollution Control Loan Fund, which helps to fund the cost of updating home septic systems, McGarry said.

“That has been a godsend, really, because septic systems aren’t cheap anymore,” McGarry said. “A lot of people cannot afford them, so it really does help out in those situations.”

The program has allowed the health department to upgrade over 200 home septic systems for property owners who meet financial thresholds and live in the home.

“We’re not going to let landlords take advantage of their lack of keeping up with the maintenance of the systems,” McGarry said.

According to McGarry, the two biggest red flags of a failing septic system are a foul stench and soggy ground. A properly working septic system should produce few scents, and if it does smell it should smell like one’s laundry detergent.

The soggy ground would come from a broken leach field, a series of pipes with small holes in them that distribute treated waste below the ground. Ordinarily leach fields only result in greener grass in their vicinity, but a broken system will oversaturate the ground.

McGarry encouraged members of the public to call the health department if they are worried about their septic systems. He acknowledged, though, that people fear the consequences of such a call.

“I think the biggest challenge in this is that homeowners look at us as 100% enforcement,” McGarry said. “So people are very hesitant to reach out to us, either neighbors, family members or the individuals themselves. They think we’re going to come in and leave them with a $15,000 bill.”

The department isn’t out to bust people, McGarry said — it just wants to help.

“We, first and foremost, are all educators, and we want to educate the public on these systems,” he said. “Even if we do have a nuisance complaint, we’re going to see what we can do to mitigate it at the least amount of cost to them. All of us live here, none of us want the pollution”

Kruse Daniels echoed that sentiment, encouraging more investment in septic infrastructure.

“With septage and other wastewater, it does come down to investment in infrastructure,” Kruse Daniels said. “You know, seeing the value in investing in infrastructure for people’s health, for economic development and for your communities.”

Let us know what's happening in your neck of the woods!

Get in touch and share a story!