ATHENS COUNTY, Ohio — Spotted lanternfly will soon arrive in Athens County if its spread across Southeast Ohio continues at current rates.

Since the invasive species was first documented in Pennsylvania in 2014, it has migrated across the Midwest and East Coast with reported populations in Illinois, Massachusetts and North Carolina.

Native to East Asia, spotted lanternflies (Lycorma delicatula) pose a threat to dozens of commercially important plants. In 2019, researchers at Penn State University estimated that a statewide infestation could cause up to $324 million in agricultural damage.

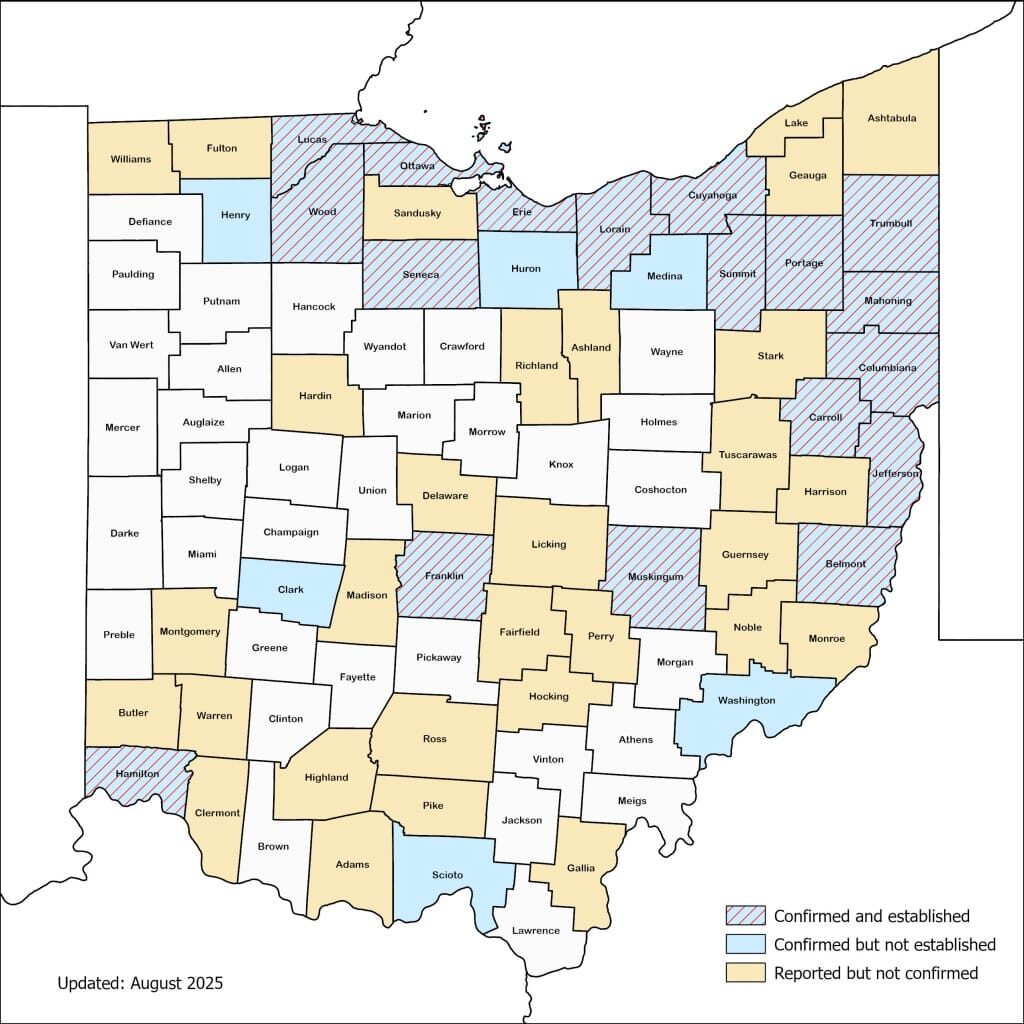

The Ohio Department of Agriculture confirmed the state’s first spotted lanternfly infestation in Jefferson County in 2020. Since then, spotted lanternfly populations have been observed in Columbus, Cincinnati and Cleveland, according to the Ohio Department of Agriculture.

Spotted lanternfly has primarily spread by stowing away on cars, trains, commercial trucking and airplanes.

“Spotted lanternfly is really good at hitchhiking,” Johnathan Shields, the spotted lanternfly program manager for the Ohio Department of Agriculture, said. “They seem to spread along transportation corridors. So we find populations along rail lines, along highways. When you zoom out and look at the national spotted lanternfly picture, you can actually see those transportation corridors.”

In Southeast Ohio, spotted lanternfly has spread slowly, with sightings confirmed in Washington and Scioto counties in 2025. Gallia, Hocking, Noble, and Monroe counties have all had reported sightings of spotted lanternfly, but these reports haven’t been confirmed by the Ohio Department of Agriculture.

“We’ve been identifying [spotted lanternfly] in some additional new counties this year,” said Shields. “We’re continuing to receive a lot of reports of spotted lanternflies that we try to follow up on as quickly as we’re able.”

Athens and Hocking counties may prove particularly important, given the tourism industry and the number of travelers that visit the area each year.

“Athens and Hocking counties are destinations for travelers, especially from areas where spotted lanternfly might be more established. There’s going to be a risk of [tourists] transporting lanternfly there and it then getting established,” Shields said. “For visitors to Athens and Hocking counties, we would encourage those folks to check their vehicles for spotted lanternfly.”

Ashley Leach, an associate professor of crop entomology at Ohio State University, has been working with farmers to combat the spread of spotted lanternfly. Leach told the Independent that a key part of managing spotted lanternfly is accepting that human-assisted spread is going to happen no matter what.

“If we could stop the humans from moving, then we could stop the bugs from moving,” Leach said. “But the reality is, that’s not going to happen, and that’s fine. So I think we need to be in a place of, ‘Hey, we’re probably moving this bug indirectly, and we don’t realize that. Let’s make sure we’re being a little bit more vigilant about what’s in the car and where we were parked,’ you know, that kind of thing.”

Shields encouraged the public to report sightings of spotted lanternfly, suggesting that anyone who finds the insect take a picture of it, then step on it.

“Stepping on them and squishing them is a great way to deal with them,” Shields said. “We have a spotted lanternfly management guide on our website that has some really useful advice [for the public].”

Spotted lanternflies’ impact on ecology and agriculture

The spotted lanternfly is related to aphids, Leach said. Both are small, sap-sucking insects that don’t immediately harm other animals, but damage crops and other plants.

“It’s only going to be going after plants. It can’t bite people,” Leach said.

For farmers, this means that spotted lanternfly is yet another pest they need to keep an eye on and find a way to prevent from killing their crops.

“The greatest impact of spotted lanternfly would be to grape growers,” Shields said.

Leach has written about a few different methods growers can use to prevent or eliminate spotted lanternfly infestations:

- Using pesticides such as neonicotinoids, pyrethroid, and organophosphates.

- Destroying spotted lanternfly egg masses when they are found.

- Removing vegetation that spotted lanternfly likes, such as tree-of-heaven.

- Installing exclusion netting to keep spotted lanternfly from reaching the crop.

Spotted lanternfly gets its food from over 100 different plant species, but shows a preference for tree-of-heaven according to Shields.

Tree-of-heaven is also an invasive species in the U.S., originally coming from China. It’s also a particularly tough plant to remove, due in part to its high seed production and its practice of releasing toxic chemicals into the soil to prevent other plants from growing nearby, according to the Invasive Species Center.

While spotted lanternfly consuming tree-of-heaven may seem like a good thing, tree-of-heaven gives the insects a place to congregate and reproduce. And if spotted lanternflies devour all the tree-of-heaven in an area, they would move on to other plants — probably native ones, which would harm the local ecosystem.

Another downside to the spotted lanternfly’s appetite for tree-of-heaven is that feeding from the trees gives the insects toxic properties, research has found. This makes the insects less appealing to predators.

While this toxin discourages predators, Leach said, it doesn’t completely stop them. Praying mantises, spined soldier bugs, raccoons and birds are frequently seen eating spotted lanternfly. Still, the local ecosystem has no natural predators for spotted lanternfly.

“What’s going to naturally keep those populations in check [are] those endemic natural predators, parasitoids that are from Asia that have kept this bug in check there,” Leach said. “We really need to figure out if that’s possible here.”