ATHENS COUNTY, Ohio — Copperhead snakes are responsible for the most snake bites each year in the United States, they are also some of the least deadly — and live right here in Athens County.

Doug Wynn, who has written and edited multiple books about the state’s amphibians and reptiles, has been researching copperheads since the 1970s and participated in over 250 research projects focused on snake conservation in Ohio.

Wynn offered simple advice on what to do if you encounter a copperhead in the wild: Appreciate it from a distance.

“Take out your cell phone, take pictures of it,” Wynn said. “Take advantage of the situation, [copperheads] are cool.”

The Eastern copperhead is one of the three venomous snake species that call Ohio home, and the only that calls Athens County home. The snake is primarily found in Southeast Ohio, often on dry, rocky, remote hillsides.

Copperheads are a type of pit viper, with copper-colored heads and brown hourglass patterns on their bodies. This coloration allows them to blend into the forest floor and rocks, making it easier to ambush prey.

Copperheads occupy a spot in the lower middle of the local food chain. The snakes eat bugs and small rodents; copperheads are eaten by birds, possums, coyotes and other animals.

Although copperheads tend to avoid people, they will move into abandoned and neglected human structures, Wynn said.

“If humans abandon [an] area, they’ll move into [it],” Wynn said. “Whereas something like a timber rattlesnake is so picky that they’re less [likely to move in].”

The Moonville Tunnel, for example, is known for copperheads, he said.

To keep copperheads from moving onto your property Wynn has a simple recommendation: “Keep your yard clean [and] keep your property clean.”

Venom and bites

According to the Centers for Disease Control, roughly 7,000–8,000 people annually are bitten by snakes. The most cited number for copperhead bites comes from a 1967 study, with roughly 3,000 bites each year attributed to the snake — making them the most common source of snake bites in the United States, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

Fortunately, copperhead bites are almost never fatal.

Despite this relatively high bite rate, a small number of fatalities each year are due to copperhead bites. The same 1967 study reported that 0.01% of copperhead bites result in fatalities.

Wynn said this low fatality rate is primarily due to the relatively small amount of venom copperheads inject.

“It’s estimated that the average venom yield is 30 milligrams,” Wynn said. “But [experts] estimate it takes 40 milligrams for a person to be bitten, go without treatment and die.”

Additionally, copperhead venom is relatively mild compared to venom from more dangerous snakes, such as cobras, whose venom can impact the respiratory and musculoskeletal system.

Instead, copperhead venom causes pain, progressive swelling, skin redness, bruising, and blood blisters, according to the National Poison Control Center.

Copperhead bites require antivenom about half the time, said Nathan Lowien, an emergency room doctor at Ohio Health O’Blenness Hospital in Athens.

“Copperhead venom causes local tissue inflammation and damage,” Lowien said. “There’s an immune response along with it; it can cause hemotoxicity, meaning making your blood not clot the way it should, and causing bleeding risk.”

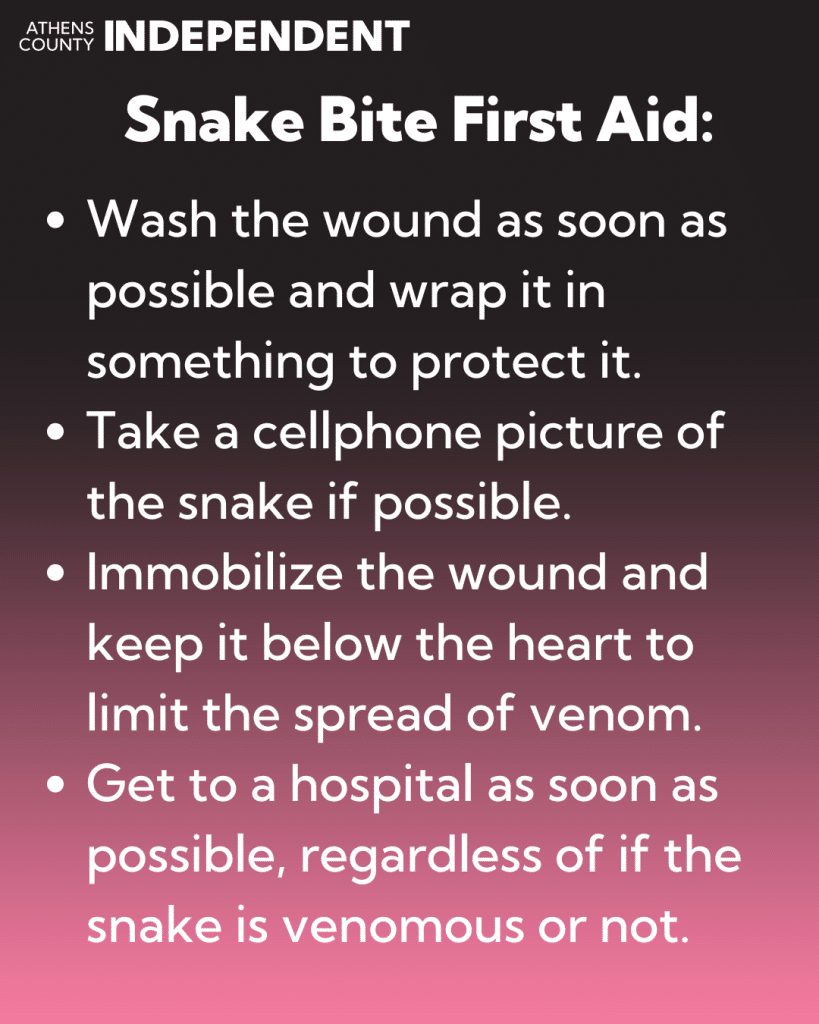

Lowien had several recommendations for the public when it comes to treating a snake bite:

“[Going to a hospital is] always the recommendation — it’s better to be safe rather than be sorry,” Lowien said.

O’Blenness keeps a regular supply of CroFab, an antivenom used to treat copperhead bites, Lowien said. “There isn’t another good [antivenom] for relatively severe copperhead bites,” Lowien told the Independent in an email.

Lowien explained that CroFab is created by injecting sheep with the venom of four different North American pit vipers. The sheeps’ immune systems create antibodies to counteract the poison; those antibodies are then isolated and tested for any potential viruses, before being used as antivenom.

After the administration of antivenom, the patient may be kept in the hospital for 12 hours for observation “to see if something happens,” Lowien said. “You don’t want to have enough swelling to cause problems with blood flow to your arm or develop blood clotting issues or things like that.”

The antivenom itself can cause problems, Lowien noted. Because it is derived from sheep, this antivenom may pose a problem for people who are allergic to sheep. And it’s possible people may be allergic to the antivenom itself.

A medical case write-up documenting an allergic reaction to CroFab noted that a patient was able to tolerate another type of antivenom, which is sourced from horses.

However, the same case study notes that it’s also possible that patients reacting to CroFab may have α-gal (Alpha-gal) syndrome, more commonly known as the “meat allergy,” as the α-Gal galactose is a common ingredient in antivenom.

To head off potential allergic reactions, Lowien said, “We would probably pre-treat the allergy with steroids and antihistamines and monitor for re-dosing or additional treatments if an allergy developed.”

People who keep exotic venomous snakes as pets don’t have a local treatment option, as O’Blenness doesn’t carry antivenom for non-native species, Lowien said.

The hospital would have to get specific antivenom through the poison control center or the Columbus Zoo, which keeps exotic snake antivenom in case one of their specimens bites someone, Lowien said.

Snake bite myths

Wynn and Lowien both noted that there are a few well known methods of treating snake bites that are completely false and might make the emergency worse.

- You can’t suck the venom out of a wound by cutting the bite, sucking in blood and spitting it out. “You risk additional infections if you do stuff like that,” Wynn said.

- The shape of the bite does not indicate if the snake is venomous or not. “You can’t tell a venomous bite from a nonvenomous bite by the initial appearance of the wound in terms of fang marks or lack thereof,” Lowien said. “That’s not reliable, and it can be hours before developing symptoms, and they can come on and be rapid.”

- Juvenile copperheads are more dangerous than adult copperheads as they can’t control the amount of venom they inject. A fact sheet from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources states, “Copperheads of any age are capable of controlling the amount of venom given in a bite, and ‘dry bites’ (where no venom is given) occur frequently with this species.”

- Put a tourniquet on the affected limb to keep the venom from spreading around your body. This myth can actually make things worse, according to an article from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “[This is because the tourniquet] keeps all of the toxin in one place and gives it more time to cause damage. It also cuts off blood supply to any healthy tissue, causing more damage,” the article states.